I don’t know. I guess I just wanted to, like, hear someone say it. Even if they didn’t say it directly.

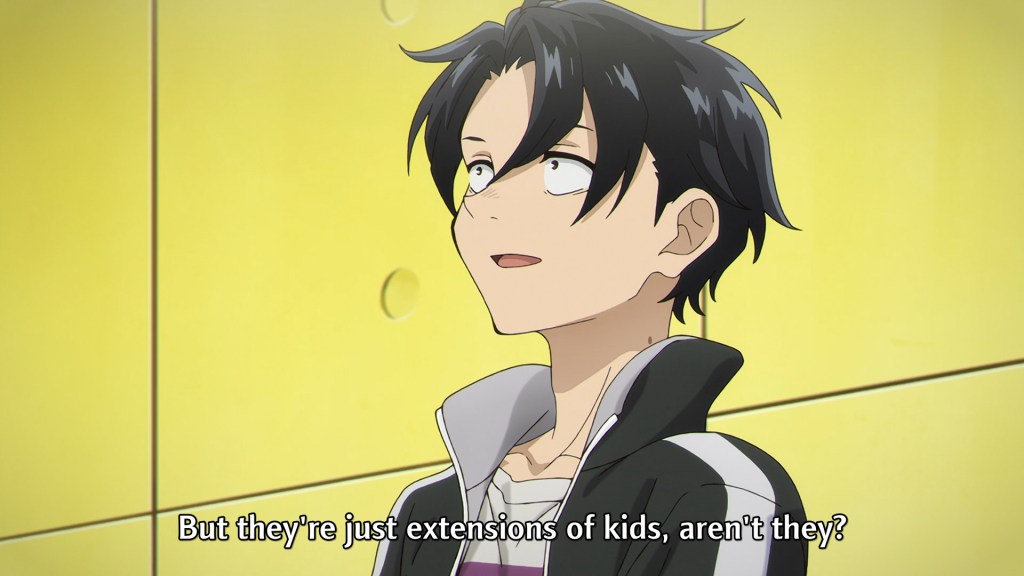

In the final episode of the second season of Yofukashi no Uta (aka Call of the Night), as the formerly murderous detective Anko Uguisu lies exhausted by her long, now-failed quest for revenge next to him, 14-year-old protagonist Kou makes the following observation:

“I used to think adults were like, an alien species. But they’re just extensions of kids, aren’t they?”

It’s one of many closing reflections Yofukashi no Uta meanders through in its final episode, but I personally found it the most endearing and touching.

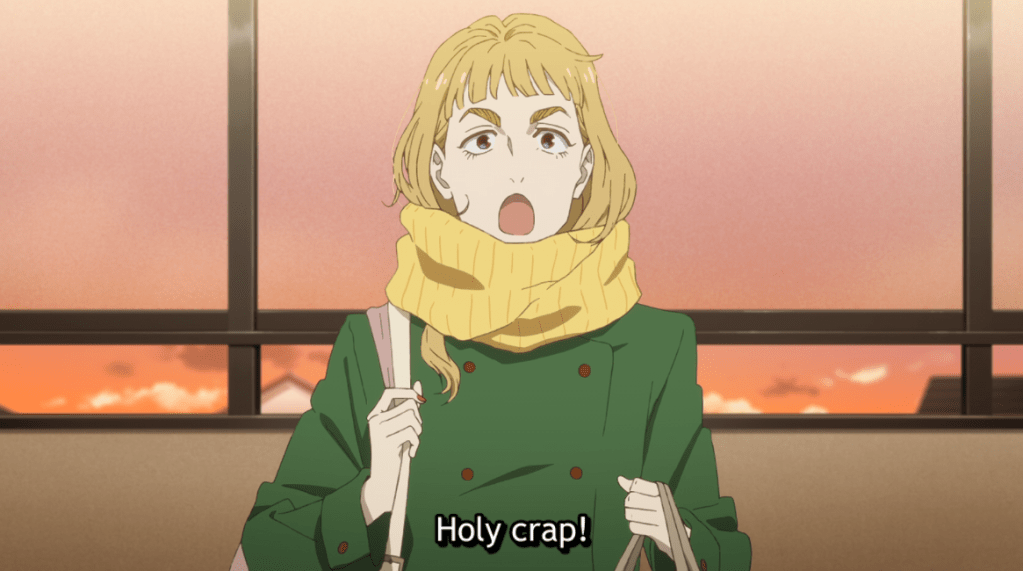

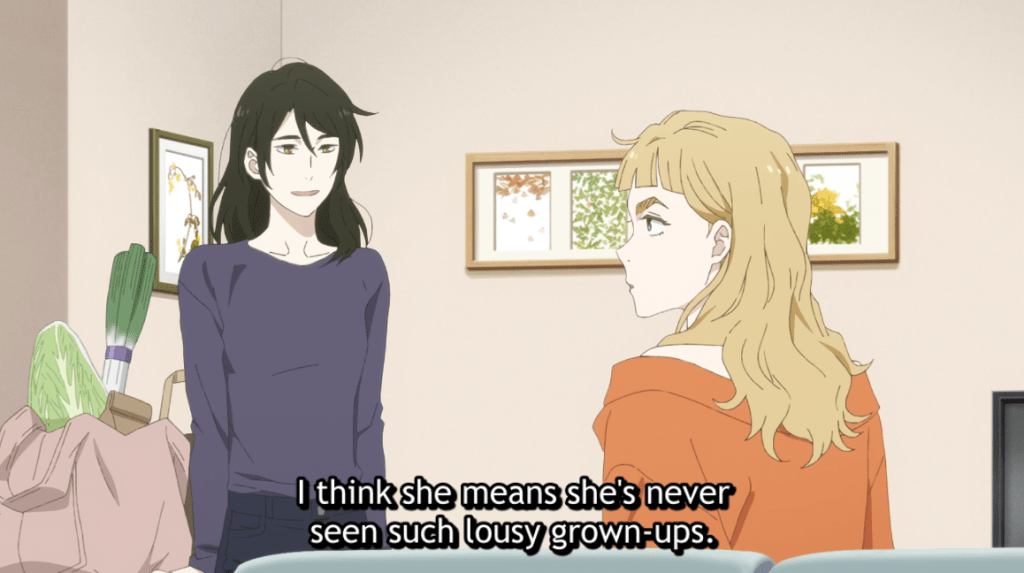

Skip forward to this season, and the second episode Ikoku Nikki (localized as Journal with Witch) offers a similar perspective on adults through a young adult’s perspective, as the recently orphaned Asa (15 years old) experiences a conversation between her aunt Maiko and her aunt’s friend, Daigo, as being like listening to people on a street in a foreign country speak in an unrecognizable language. “This is how grown-ups talk?“ she wonders as she witnesses Maiko and Daigo both talk to and past each other.

Half my lifetime ago (or perhaps even less), I might have found myself more aligned with Kou and Asa in their fresh discoveries of adults. Nowadays, though, as someone much closer to Anko and Maiko’s ages than those of the kids involved with them, there’s a kind of almost comforting feeling that comes from being observed in such a way. Of course, it might be a little self-deceiving to label these scenes as being “observations about adult by children.” It’s adults who are writing these stories, after all.

Even so, I like that Kotoyama and Tomoko Yamashita choose children as their mouthpieces. As a viewer, it invites me to consider the observations not simply on their own terms, but specifically from Kou and Asa’s points of view. In other words, it suggests that their thoughts might be ideas that young people more generally might have about adults. There’s a certain benevolence that comes with that, as if there are ways adults can be that prompt feelings and impressions in children other than intimidation, fear, and obstruction. Or, maybe it’s simply that it feels more natural to consider what being an adult means from the position of where we came from, more comfortable to align oneself with the viewpoint of the young.

I don’t think (in fact, I know) I’m not alone in finding the transitional road from being a teen to a young adult to just an “adult” much more murky that it’s often made out to be. So many of us have been provided the expectation that line between childhood and adulthood is like a door you open, a distinct threshold which, once you’ve passed it, signals clearly that you are now One Thing rather than What You Were Before. Of course, this is nonsense, but it’s a common way of thinking that causes quite a lot of mental struggles. How can you know when you no longer inhabit one status and have become a different kind of human being?

There’s a question of identity here, too, not to mention the concerns of the impermanence of the self. It can feel rather scary to take on the label of “adult,” as doing so can feel like putting aside certain traits perhaps more commonly thought of as childish—wonder, joy, the ability to find humor in life, flexibility of mind, excitement, perhaps even a certain degree of (endearing or not) selfishness, and so on. Does accepting me-as-adult mean dismissing me-as-child? Must the part of me that I still remember, the part, perhaps, that loves having fun in the middle of the night, vanish entirely in the face of the part that knows I have to go to bed at 10pm in order to wake up for work the next day?

But if Kou Yamori is to be believed, perhaps we never fully quit being children. If adults are only extensions of children, rather than being an incomprehensible, alien species, entirely different organisms, then perhaps that means we are all only moving slowly along a spectrum with no end to the gradient. Perhaps we are all mixtures of the child and adult in different measures, with all the joy and pain the comes with it.

Still, I wonder if there is an element of privilege or naïveté or convenience to such a conclusion. It might be too good to be true. It might be a dream that fades with night’s end.

This is where the idealistic, fanciful nature of Yofukashi no Uta is greeted by the more somber, more grounded world of Ikoku Nikki. Not that Kou and Nazuna live in a world without conflict, but it’s not hard to argue that Makio and Asa inhabit a story more adjacent to reality. In Ikoku Nikki, no one goes seeking revenge for the death of Asa’s parents; all that remains is resentment, and the sprawling desert. Grief… uncertainty… responsibility… these are more familiar weights, ones more like the burdens we all carry.

Perhaps that’s why the appearance of Daigo and the casual, almost crass way she speaks with Makio is both so shocking to Asa and so soothing to me. It may be that to Asa, so used to the stiffness of her home and parents, Makio and Daigo might as well be an alien species. But, to me, I see a reflection, if incomplete, of the kind of person and adult I see myself as at this point in my life. It’s hard to give up on the idea of being young, or at least youthful, and even harder when adulthood allegedly means becoming something altogether than what you have been. If being an adult means becoming someone like Asa’s mother, I’d rather be one of Makio’s “lousy grown-ups.” But if even adults can be like like this, then maybe being an adult doesn’t have to be so scary.

It’s all the more meaningful when this interaction comes in the wake of Makio making the decidedly grown-up decision to take responsibility for Asa, even if she did so only on a whim. If a certain level of selfishness is inherent in being a child, then surely the focus on the other in a line like “You’re deserving of much more beautiful things in life!” must be a quality of adulthood. Then again, at this point in Ikoku Nikki‘s story (episode 2), it can hardly be said that Makio is doing an exceptional job. She has her own selfishness, as can be seen by the way she “makes” (in her words, even though it’s not quite right) Asa clean the house.

In fact, maybe another way of looking at Makio’s adoption of Asa is to see it as childish—the consequence of an anti-social, defiant outburst rather than any well-reasoned, carefully considered decision. Although she’s undeniably done something good for Asa in providing her with stability she might otherwise have lacked, she’s also clearly unsure of how to actually meet the needs of the young person now in her charge. Daigo needing to suggest to Makio that she reach out to her ex, Kasamachi, is evidence of this. Makio is being adult, yes, but haltingly. All of this exists alongside the version of her that appears in Daigo’s presence, which one can’t help but see as her at her most open.

In the end, I suppose that contradiction, that lack of a clear cut image of an adult, might be the idea that both Yofukashi no Uta and Ikoku Nikki are getting out, the latter demonstrating in mundane, grounded terms the same conclusion the former’s fantasy tale arrived at. It may simply be that no true definition of “adult” exists in a qualitative sense, despite the legal lines drawn based on age.

I don’t have any grand conclusion to make at the end of this. If anything, this is simply a post of appreciation of the ways these two shows made me feel a little seen as someone who is probably no longer considered a “young adult” by the world but still feels the heavy label of “adult” is something I’d rather not welcome. Accepting that label is scary. I don’t want to do it. So I’m thankful that Kou and Asa, Anko and Makio and Nazuna are here to tell me that it’s okay.

In the end, we can only be ourselves as we are and carve out those identities as best we can in the face of everything we encounter, whether that be vampires or loss.

[…] Taking Comfort from Perspectives on Adults in Yofukashi no Uta and Ikoku Nikki – musings on how Call of the Night and this season’s Journal With Witch both, in their different genre contexts, draw attention to the arbitrary social definitions of “maturity” that position adults as an alien species from the teenagers observing them. […]

LikeLike