It’s never explicitly stated, but at the end of Glasslip, at the conclusion to a brief and fitful summer, Kakeru Okikua leaves town to continue accompanying his famous piano mother as she tours the world… just as he has always done. Behind him, things have changed forever in the group of friends. It’s a momentary glimmer, but the effects will live on long after the sparkle has faded.

Glasslip is a reflection on the nature of time. It is about the impermanence of life, about the transience of our temporal existences, about the significance of these fleeting events of the past we call memory.

Even before the first episode of Glasslip had aired, its title was something of a mystery. “Glasslip.” A word with a pretty sound (using either the English or the Japanese pronunciations), it was at once evocative and nonsensical. For the longest time, I supposed the proper pronunciation of it was “glass lip,” a lip made of glass (whatever that meant). I confess it was not the most convincing or satisfying of interpretations. However, having once again seen the show through, having once again seen the way it presents itself from start to finish, I find Glasslip better read as “glass slip.” Just as scenes glide into each other and characters drift from state to state, the title slips from word into word. And time slips by.

I say Glasslip is about impermanence and transience, not change, and I say so deliberately. Glasslip is far less about the changes that occur in the lives of it cast and far more about the fundamental condition that lies beneath them. Life passes us by—is always passing us by—and yet we are so often unaware of its slow and constant ebb. Even those of us who have apprehended its motions are rarely always conscious of this reality.

“You seek a mainstay and a permanent law in the temperate mid-region of our earth, but here, too, there is nothing but constant event and changing history, and no one can forecast for you even next week’s clouds.”

—Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World

Glasslip lives in and is constantly aware of this slippage, of the ever flowing moments we live and cannot reencounter. From the moment Kakeru first passes by Touko Fukami at the festival in the first episode, it’s clear that Glasslip believes intrinsically in a state of existence in which things and people pass us by, sometimes connecting only for a moment. Like the sharp boom of fireworks, these fragments of existence are whisked away from us in the next moment, leaving us barely a moment to consider them or decide how we should respond. As Glasslip see it, we exist in eternal motion, where the question always being asked is: “What meaning does this all have?” For the audience of Glasslip, this question is similarly one which the show invites the watcher to ask of it. Does Glasslip mean anything at all, or is watching it simply an act of pushing a boulder up the hill, only to see it roll back to the bottom at the end of each episode?

I say yes. Glasslip does have meaning, but it’s a meaning communicated in fragments.

This is not a show content merely to tell the story of a group of young adults coming to grips with the reality of change in their lives—it is a meditation on impermanence and transience, and it is constantly working to cultivate a wistful, ephemeral atmosphere, one in which the show itself passes by almost like a dream or a vision. The motions of each episodes weave into each other; seemingly unrelated scenes intercut with each other, dwelling on screen for just a few second before returning to the main action. Everything—often connected by the same musical track—is constantly bleeding into everything else. On the surface, episode after episode gives the impression of incoherency and disconnect, while the subtle undercurrent of slipping time holds it all together.

How does Glasslip achieve such an effect? How can fiction fragmented hold together? The answer in this case is through the use of motifs; that is, recurring fragments. These are not the techniques of a show devoted to a specific narrative path, but rather the toys of an artifact committed to an experience conveyed through experiences, an oft-unrealized reality played out through aesthetic constructs. But motifs and ideas don’t matter if they aren’t accompanied by—that is, allowed to flourish through—execution. And Glasslip‘s execution is where the show truly shines, embracing the transient and the impermanent completely. The isolation of moments, the casually impenetrable dialogue, the number of scenes that function on image and sound alone… all of these contribute to an ethereal, meditative atmosphere. By leaning into its repeated motifs, by returning to images, sounds, ideas, and chickens, Glasslip is able to highlight those things that move by way of contrast with those things that stay the same.

Among the show’s visual-conceptual motifs, two stand out: trains and the town.

Nearly every episode of Glasslip returns to the image of a train on the tracks, coming and going. It is on a train that Kakeru arrives in the first episode, and the episodes that follow frequently use shots of the train coming and going as establishing shots or as transitional shots between different scenes. Like time itself, the train is always in motion—its constant is that it never remains still. But the image of the train doesn’t just exist in the abstract, but is deeply connected to two of Glasslip‘s main characters—Yukinari Imi and Yanagi Takayama. From the very start of the show, Yana (the member of the initial group most inclined towards motion through her desire to become a model) has been riding the train daily to her various lessons—it is her river of time. Later on, the Hinode bridge (which becomes both the location where Yana confesses as well as Yuki and Yana’s place of connection in both the real world and the alternate reality of Touko’s vision in the penultimate episode) takes on a similar type of symbolism; it is, after all, a bridge over train tracks. And in the eighth episode, recovering runner Yukinari Imi takes the train to a running camp so far away from his hometown that the weather can be entirely different.

The town itself—seen frequently from an aeriel view at different times of day—is associated with the sickly Sachi Nagamiya and the boy who loves her, Hiro Shriosaki. Together, these two embody the spirit of the town: far less dynamic and drastic in its slow march through time, but no less incessant. It fits these two perfectly. While Sachi is too physically weak to ever effect momentous change (even her attempt to upset the love affair of her best friend fails due to her condition), Hiro is correspondingly glacial in his movements due to his insecurity. And yet, both of them inch forward. “For tomorrow” becomes the shared catchphrase of their eventual mutual affection, a emblem of their slow-moving, but never still relationship. There are no bursts of motion, there is only steady, constant change—like the gradual turning of the day.

Time flows, but its motion is not the same for all.

Although Yuki and Yana, Sachi and Hiro are all ancillary to Glasslip‘s musings on time, it is in the characters of Kakeru and Touko, along with their own associated motifs, that the reflection on impermanence truly finds its voice.

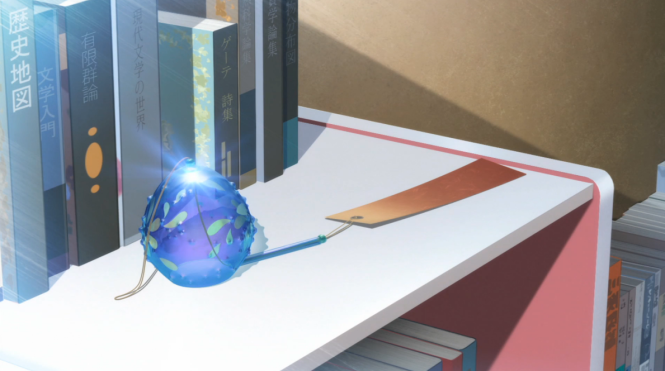

Touko and Kakeru see and hear. Visions, sounds…fragments of the future, or not. For Touko, these bursts of image come from reflections and light—most often and most powerfully, through the shimmer glass she’s lived with her entire life. Kakeru similarly finds his “fragments of the future” amidst the sounds of life, but experiences their effects most powerfully through his mother’s music. The two unified constants of their lives lead them into the profoundly inconsistent fragments. And how perfect it is that their mediums (the motifs of their lives within the show) would be such fleeting things. The sudden-and-vanished flash of sunlight off the side of a car… the momentary presence of a piano’s chords… light and sound, by their natures beautiful expressions of the transience of time.

“Trust time. Time is music, and the space out of which it resounds is the future. Measure by measure the symphony is created in a dimension that inverts itself, and which at each moment makes itself available from the unfathomable store of time. […] You cannot interrupt music in order to catch and hoard it. Let it flow and fleee, otherwise you cannot grasp it. You cannot condense it into one beautiful chord and thus posses it once and for all. Patience is the first virtue of the one who wants to perceive. […] For look: you cannot grasp the melodies flight until its last note has sounded.”

—Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World

And thus it is for the impatience of Kakeru—who seeks to understand himself and his “expected-unexpected loneliness”—and of Touko, who is impatient only for things to stay the same. But by the show’s end both find themselves disappointed in their particular questions, and both find themselves embraced again in the flow of time, finally comfortable in impermanence and welcoming of the moments that are perpetually trickling by. Kakeru can grasp neither his present, his future, nor the music his mother plays. The chords hang in the air, then tumble by into new chords. In parallel, Touko sees in the heartbeat flash of light through glass. As time appears to them, it speeds away. And this is the reality they eventually come to grasp.

Initially, Kakeru (although his understanding is incomplete and dissatisfying to him) understands this far better than Touko, who has lived her entire life in one town amongst one unchanging group of friends. Touko is place-bound, Kakeru is free. Kakeru desires what Touko has, or what it represents, and Touko seeks to keep that very stasis. Of course, the irony is that in her attempts to resist time’s flow, she is left behind by it. Her friends change outside of her grasp and her desire to understand her visions and to reach out to Kakeru push her towards actions that ultimately mean she cannot maintain the very thing she seeks to keep. She desires to reach to Kakeru without seeing her world change—but it is a wish that cannot be, because both of them embody transience, even if Touko is unaware of it.

All of this comes together in the show’s penultimate episode, with Touko now in Kakeru’s role as the outsider, as the newcomer, as the trespasser in a place protected. She meets her friends, but they do not know her, nor do they remember her when she encounters them later. And the vision she sees of this alternate world’s group ends up nothing but an illusion. In the reality of this alternate world, the waves of time have pushed them apart even as they remain connected by their desire to be together and by the fireworks they all view from their respective points of view. A tradition has been broken… but this is nothing but the natural order of life. And through this visceral experience of the transience of Kakeru’s existence—suddenly appearing, just as quickly forgotten—Touko finally comes to realize just how impossibly fragile the single moment is.

As a whole, Glasslip understands this fragility well—but it also refuses to devalue these moments because of their transitory nature.

In episode 6, Touko inquires her mother’s opinion on her supposed visions of the future, asking what it would be like to live out a romance movie where you already know the answer. “I don’t know what you’re talking about, but if you did, you could enjoy it twice,” her mother responds (emphasis mine). But, of course, what Touko has been seeing is not the future and, as she discovers, she can’t relive her first kiss twice. The kiss she shares with the Kakeru in her vision is a terrifying one, but their real first kiss is tender and gentle. And it, like many other moments throughout the show—some seemingly trivial and others, like this one, clearly of importance—is immortalized in a still frame cast over with lines of light, like a painting. A single moment, unique and irreplacable. A moment, crystalized and briefly held

These moments, insignificant as they may seem to those outside, are immortalized both at random—we see Touko held in a freeze frame looking up at the gulls above the beach in one episode—and for their gravity. And all are equally important. Life is not made of things that last, but of things that are once held and then pass by, leaving their mark and their memory.

Impermanence ought not be equated with irrelevance.

“What strange beings we are! We grow only by being thrust into transiency. We cannot ripen, we cannot become rich in any way other than by an uninterrupted renunciation that occurs hour by hour.”

—Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World

So, what does all of this mean for our lives? At the end of their final conversation, Yuki, having finally moved on from his crush on Touko, tells her: “You haven’t changed at all. Or maybe you have?” And, really, this in the truest expression of what Glasslip is saying about time and our experiences within it. The modulations of impermanent time are difficult to apprehend; they are small and slight by nature, and go easily unnoticed even by those to whom they impact most. But they are real nonetheless, and they define us whether we wish them to or not. Like the river of time, we never truly stay the same—and yet we never entirely cease to be ourselves. We are here and yet not here, moving and yet still.

When Kakeru arrives in the cafe at the end of the first episode, crashing into the stability of the group liken an ambassador of a life unsettled, he does not disrupt—merely alters the slow forward inertia of a few members of the group. He is the very antithesis of them: solitary, blunt, confident, unbound by place—an outsider. He is the lived experience of time come and gone—”expected unexpected loneliness,” the paradox of the surprise of the unavoidable. He lives in the very flow of time and brings this river with him, crashing over the steady rock of their static high school lives.

Glasslip allows us to see the results of Kakeru’s arrival, to witness not only the realization of time’s impermanence through he and Touko’s experiments, but also its effects through the changes that ensure in the lives of Yana, Yuki, Sachi, and Hiro.

Yana, being the one most inclined towards change—the trains are always running, after all—ends up being the one most impacted by Kakeru’s arrival. His presence (its motivating effect on the normally static Yuki) serves as the force that moves Yana to reach forward—and in that effort she transforms. “You’re… leaving after you graduate, aren’t you?” Yuki asks her in episode 11, having seen one of her lessons for the first time. As with Kakeru’s departure at the end of the show, the answer is left unsaid, but clear. Finally, Yuki understands. Yana—the one most inclined towards change—has entirely accepted the embrace of time (her nude walk through her house is a poignant example of precisely this), whether or not it brings her the things she wants most.

Ultimately, Yuki cannot help but be caught up in the flow of time along with Yana. Despite fleeing to the bubble of the running camp, Yana is always calling him back into time. And we can see how things have shifted when he returns, witnesses Yana out on her run, and awaits her at home in a reversal of their prior relationship. Yet despite how everything has changed; nothing has—and the two of them share a moment of real connection that only the ambling steps of time could have imagined. Time brings all things together.

Sachi and Hiro, as the slowest movers in the group, take their time throughout the show. For them, Kakeru’s arrival merely upsets a balance they were used to, but never held down by. It is a passive acceptance of their impermanent states, and they trickle forward to their ending.

Of course, Glasslip could not be complete without showing the future of a life lived in acceptance of the transience of time—and, as if to give clues along the way—this humble wisdom exists alongside the young protagonists of the show constantly in the form of Touko and Kakeru’s parents.

They have lived long enough, seen enough life pass by them, to both understand and accept this reality. And, perhaps more importantly, they are also wise enough to allow their children to come to terms with this themselves. In the final episode of the show, a meteor shower in the sky parallels Kakeru and Touko’s last experiment: the tossing of Touko’s glass beads into the air. As they do so, Touko’s parents look at that the sky along with Hina. While Hina is overjoyed at the sight of the meteors, her parents reminisce about the moment when Touko’s father proposed to her mother. Like the meteor shower, it was but a single instant in their lives—but, as Touko comes to understand, even those smallest bits of time can mean a great deal.

Then, how do we respond when in moments of clarity we truly feel the unyielding flow of time coursing through and around us? Although we may become aware of it—as Touko and Kakeru do through mutual influence on each other—and come of age, not sexually, but existentially, we cannot ever really understand it. By its nature, time is impossible to grasp. How do we deal with a reality we can see only in flashes, hear only in passing notes? For Glasslip, the answer lies in trusting in the significance of the moments that come our way, while striving to never tie ourselves to them completely. Although our moments always replaced by the forward momentum of the next realization, the next change, the next step forward, or the next moment, they are not insignificant. They mean something. They represent the pivots on which our worlds and our experiences of them turn. Kakeru departs at the end of Glasslip, but his doing so does not negate the fact that he was there, nor does it erase the impact his presence—however brief—made.

It may have just been the glancing sparkle of sunlight on glass, but is was still beautiful.

That… was beautiful. Wipes a tear

(Hello! I think the last time I dropped by was when you were blogging Yona/KimiUso.)

I never hated Glasslip like most viewers seemed to. I’d always likened the show to certain short stories by my favourite writers (Jhumpa Lahiri especially- if you haven’t read her work, I highly recommend them) in the sense that it focused on “the little things in life”. But Glasslip was harder for me me to pin down, mostly Lahiri’s short stories usually focus on two or three individuals at most, while Glasslip had several loosely interconnecting stories involving a group of six. I think the overall ambience (which I remember really liking, even when the show was puzzling me) managed to convey the impermanence and fragility of those moments better then the dialogue ever did. “Fleeting” was probably one of the words that occurred to me when I was watching Glasslip, but I don’t think I would have been able to expand the concept’s relevance to the show as thoroughly and as magnificently as you have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

** “expand on. Gah I wish WordPress had an edit option.

LikeLike

🙂 Thanks for your kind words! And welcome back!

I definitely agree that the show’s ambience is a big factor (perhaps even the main one) in conveying the shows reflections on impermanence. While I think the show’s overall structure is quite solid, the dialogue itself comes off as stilted more often than not. The degree to which that bothers you depends—for me it wasn’t a big deal—but I could definitely see that being a sticking point for some.

LikeLike

I can’t believe you managed to write something deep about Glasslip

LikeLiked by 2 people

STAND IN AWE OF MY COMPULSIVE DESIRE TO FIND MEANING IN THINGS

LikeLiked by 1 person

o.0

Barkeep, I’ll have some of whatever he’s having.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It was apple juice…

LikeLike

It’s interesting to see how different people approach meaning in Glasslip. I remember you posting a link to someone interpreting it over Camus. Your very elaborate post about temporality works well, too.

I think I’d have taken security as a starting point, with the chicken-in-living-room episode early on contrasts with Kakeru-in-a-garden-tent, and go from there. But the time-aspect works better for some other little scenes, like Touko’s attention slipping during glasswork, which results in a blemish, which results in a work of art and a present to Sachi.

And I still can’t look at that marble picture without wanting to handout hardhats to Touko and Kakeru. What goes up, must come down…

Also you made me google Hans Urs von Balthasar, which was interesting.

LikeLike

Yeah, whatever you think of it, I think there are a number of really interesting ways you can approach it. Not that any of that makes it “good” per se in general, but for individual people it very well might.

I really don’t know von Balthasar as well as I’d like to or ought. Hope you enjoyed looking into him a bit!

LikeLike

I feel confused. You make Glasslip sound like an overlooked masterpiece.

I… I… I need to give it another try.

LikeLike

You can! For me, once it all came together, the whole show looked brilliant in retrospect.

LikeLike

For some reason, the whole thing with growing up and change reminds me of Nagi no Asukara (which aired just before), or at the very least Chisaki in it.

LikeLike

[…] keeps on slipping, slipping, slipping… Anime blog Mage In A Barrel took an in-depth look at Glasslip, a lazily-paced PA Works series that offers genuine profundity […]

LikeLike

Interesting. Not having seen it but knowing of it by reputation, this makes me want to watch Glasslip and see if I can see the same merits in it that you can. Onto the backlog it goes…

LikeLike

Hey, that’s why I write these things! I find something cool; I want to share it. Hopefully you enjoy it!

LikeLike

[…] one of my favorite P.A. Works anime (an unusual opinion, I know—you can read more on that on my blog), and I think it’s an excellent example of the primary character of the settings in most of […]

LikeLike

[…] one of my favorite P.A. Works anime (an unusual opinion, I know—you can read more on that on my blog), and I think it’s an excellent example of the primary character of the settings in most of […]

LikeLike

[…] written about these kinds of shows in the past. Glasslip, Gundam Reconguista in G, and Hand Shakers are each shows that I’ve valued because I […]

LikeLike

Very belated thanks. Very nice analysis/reflection on a much derided/misunderstood series.

I feel it “failed” because it was actually “gently” surrealistic but looked on the surface as if it was supposed to be a realistic SoL. To make it worse, it never “explained things”. I agree this was structured and unified by motifs (fragments at that) rather than by conventional plot logic. It felt more like a piece of classical music.

I don’t think the whereabouts of Kakeru at the end are clear — he could have moved into the house (because renovations were finally finished), he could be traveling with his mother. But I feel this doesn’t matter much — because he has found a place for his heart to rest (and return to — if he travels away). His sense of self has been transformed. And Touko has similarly been transformed — both in her notions of her self and her place.

Thanks again!

LikeLike

Yo even if it’s belated it is definitely appreciated! There aren’t many of my blog pieces that I’m more proud of than this one.

I especially like your comparison to classic music, which is interesting considering that Touko has one of her moments while listening to the piano at Kakeru’s house.

Maybe I’m due for a rewatch!

LikeLike

Someone on Reddit pointed me towards your piece — when I was saying nice things about Glasslip. I never would have found this otherwise. It really was a lovely thinng to read.

I feel that surrealism operates a lot like music. One can get a sense that there is a meaning — but the meaning tends to be just out of the reach of words. Have you seen any of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s movies. Most tend towards (surrealistic) horror — but two of my favorites are basically love stories — Journey to the Shore (a ghostly love story) and Before We Vanish (an alien invader love story). Also, did you ever follow up the suggestion (by a commenter on your DVD review) to check out Hirokazu Kore’eda? (my favorite current director)?

I guess you are only active on Twitter these days. I have an account — but rarely go there (maybe I’m too old)… (Then again, I guess I am the honorary grandfather of some folks on r/anime). My poor blog has been largely abandoned for a long time. I depended on screen shots more than text — and Blurays put an end to my screen shot capture ability….

LikeLike

[…] a name that probably means nothing to most of you until I remind you that he was the director of the infamous Glasslip, which as some of you may remember from years back, I have a lot of affection […]

LikeLike